مسجد جامع يزد [2 از 2] Yazd Jame Mosque [2 of 2] | |  همان گونه كه از عنوان و فهرست اين مقاله نمايان است، اين مقاله بخشي از يك مقاله بزرگتر با همين عنوان است كه تا كنون بخش هاي زير از آن در سايت غول آباد چاپ شده است: همان گونه كه از عنوان و فهرست اين مقاله نمايان است، اين مقاله بخشي از يك مقاله بزرگتر با همين عنوان است كه تا كنون بخش هاي زير از آن در سايت غول آباد چاپ شده است:

|

| چكيده: مطالعه كتيبه هاي تاريخ دار، بانيان، سازندگان، هنرمندان و سير تحول بناي مسجد جامع كبير يزد و انتشار عكس ها و نقشه هاي آن. واژگان كليدي: جلوخان، سردر، منار، هشتي، صحن، ايوان، گنبدخانه، گرمخانه، شبستان، محراب، قرايت خانه، كتيبه، كاشي، باني، معمار، حجار، خطاط، واقف، عمرو ليث صفاري، علاء الدوله گرشاسب بن علي بن فرامرز، سيد ركن الدين، شاه يحيي، شاهزاده محمد ولي ميرزا، سيد علي محمد وزيري، مسجد جامع عتيق، مسجد شبستاني، مسجد جامع قديم، مسجد گرشاسبي، مسجد جامع نو، مسجد جمعه، مسجد جامع كبير، يزد. Abstract: Studying historic inscriptions, commissioners, builders, artists and evolution of building of Yazd great Jame mosque and publishing its images and plans. Keywords: forecourt, portico, minaret, vestibule, courtyard, eivan, gonbadkhane, garmkhane, shabestan, prayer niche, qaraatkhane, inscription, tile, commissioner, architect, stone carver, calligrapher, bequeather, Amr Leys Saffari, Alaod Dowle Garshasb ebne Ali ebne Faramarz, Seyyed Roknad Din, King Yahya, Prince Mohammad Vali Mirza, Seyyed Ali Mohammad Vaziri, Antique Jame mosque, shabestani mosque, Old Jame mosque, Garshasbi mosque, New Jame mosque, friday mosque, Great Jame mosque, Yazd. |

| كتاب: گنجنامه، فرهنگ آثار معماري اسلامي ايران دفتر: هشتم، مساجد جامع، بخش دوم مركز اسناد و تحقيقات: دانشكده معماري و شهرسازي دانشگاه شهيد بهشتي زير نظر: كامبيز حاجي قاسمي مدير اجرايي: زند حريرچي، بهنام قليچ خاني مدير گروه تهيه و تنظيم نقشه ها: بتول ملا اسد الله، مرضيه مهدي يار نويسنده متون: مريم دخت موسوي روضاتي گروه متن: مهدي صابونيان يزد، هديه نوربخش، بابك خرم، آرش شهنواز، حسين زريني ويراستار متون فارسي: محمد پروري مترجم: كلود كرباسي ويراستار متون انگليسي: مريم طباطبايي انتشارات: روزنه؛ سال 1383 Book: Ganjnameh, Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture Volume: Eight, Congregational Mosques, part two Documentation and research center: Faculty of architecture and urban planning of Shahid Beheshti university Supervisor: Kambiz Haji Ghasemi Executive director: Zand Harirchi, Behnam Ghelich Khani Director of plan compilation and preparation team: Batool Molla Asadollah, Marzieh Mahdi Yar Writer of texts: Maryamdokht Mousavi Rowzati Text team: Mahdi Sabounian Yazd, Hedieh Nourbakhsh, Hossein Zarrini, Babak Khorram, Arash Shahnavaz Editor of Persian texts: Mohammad Parvari English Translator: Claude Karbasi Editor of English texts: Maryam Tabatabaee Publication: Rowzaneh; year 2005 |

| فهرست:

۞ 1- مسجد جامع يزد ۞ 1-1- كتيبه هاي تاريخ دار بنا ۞ 1-2- بانيان و سازندگان بنا ۞ 1-3- ديگر اطلاعات مكتوب ۞ 1-4- سير تحول بنا |

|

2- Yazd Jame Mosque ۩

|  ايوان در جبهه جنوبي صحن مسجد جامع كبير يزد. Eivan in southern side of the courtyard of Yazd great congregational mosque. Moein Mohammadi 2-1- Historic inscriptions ۩

The tile-work bequeathal inscription of the mosque, located in the eastern entrance vestibule, is dated 765 L.H (1364 A.D), the oldest date existing in the building. (1) ۞ Other stone and tile-work inscriptions in this vestibule bear the dates 770 L.H (1369 A.D) (2) ۞, 777 L.H (1375 A.D) (3) ۞, 820 L.H (1417 A.D) (4) ۞, 863 L.H (1459 A.D) (5) ۞, 875 L.H (1471 A.D) (6) ۞ and 974 L.H (1540 A.D) (7) ۞. In addition, two edicts by the «Safavid monarch Shah Abbas» dated 1004 L.H (1596 A.D) (8) ۞ and 1022 L.H (1613 A.D) (9) ۞, one by «Shah Safi» dated 1046 L.H (1636 A.D) (10) ۞, another dated 1047 L.H (1637 A.D) (11) ۞, one by «Mirza Mohammad Mohsen» -the governor of Yazd- dated 1115 L.H (1703 A.D) (12) ۞ and two other bequeathal inscriptions dated 1121 L.H (1709 A.D) (13) ۞ and 1179 L.H (1765 A.D) (14) ۞ also exist in this vestibule.

Inscriptions in the eastern portico bear the dates 819 L.H (1416 A.D), 861 L.H (1457 A.D) and 891 L.H (1486 A.D). (15) ۞ An inscription concerning restorations carried out in 1365 L.H (1945 A.D) (16) ۞ and another in kufic script dated 1370 L.H (1951 A.D) (17) ۞, which is a copy of the ancient bequeathal inscription, also appear in this portico. The prayer niche in the gonbadkhaneh bears the date 777 L.H (1375 A.D). (18) ۞ An inscription in the main eivan (19) ۞ is dated 813 L.H (1410 A.D) (20) ۞ and another inscription in this eivan bears the date 836 L.H (1433 A.D) (21) ۞. Also, an undated inscription from the time of the «Timurid monarch Shahrokh» exists in the eivan of the mosque. (22) ۞ The prayer niche in a small room called qaraatkhaneh (23) ۞ and located on the eastern side of the courtyard bears the date 890 L.H (1485 A.D). (24) ۞ An inscription recording restorations performed in 1367 L.H (1948 A.D) exists in the northern portico. (25) ۞ Also, two tombstones dated 492 L.H (1099 A.D) and 533 L.H (1139 A.D) have retrieved in the ruins of the old part of the mosque, called the «Mosque of Garshasb». (26) ۞

2-2- Commissioners and builders ۩

The various parts of this building were erected in the course of time and commissioned by different individuals. Probably the first one has been «Amr Leys Safari». (27) ۞ One of the other earliest among these to have commissioned the construction of the masque was «Alaod Dowleh Garshasb ebne Ali ebne Faramarz ebne Alaod Dowleh Abu Jafar Kalanjar» -governor of Yazd between the years 488 L.H (1095 A.D) to 513 L.H (1119 A.D)-. (28) ۞ After his dead, while in the same period, the daughters of Faramarz ebne Ali, from the «Kakui» dynasty, added other parts to the mosque. (29) ۞ Today no traces of the ancient parts remain; and the present building was commissioned by «Seyyed Roknod Din Mohammad ebne Qavamod Din Mohammad ebne Nazem Hosseini Yazdi Qazi», died in 732 L.H (1332 A.D), and completed after his death by «Mowlana Saied Sharafod Din Ali». (30) ۞ Other parts of the mosque were built by «Amir Shamsod Din Qazi» and «Amir Balaqdar» and later by «Shah Yahya ebne Mozaffar» in 777 L.H (1375 A.D). (31) ۞ The minarets of the mosque`s portico were probably built by «Aqa Jamal-od Din Mohammad» known as «Mehtar Jamal» -the minister of Yazd under «Safavid Shah Tahmasb»-. (32) ۞

|  برش افقي مسجد جمعه يزد. 1- ورودي؛ 2- هشتي؛ 3- صحن؛ 4- شبستان؛ 5- گنبدخانه؛ 6- ايوان. Floor plan of Yazd friday mosque.

1- Entrance; 2- Vestibule; 3- Courtyard; 4- Shabestan; 5- Gonbad-khaneh; 6- Eivan. | |

The building of the mosque was restored and other parts and decorative elements were added to it in different periods. The contributors to these restorations and additions included: «Zahirod Din Abu Mansour Faramarz» -the first Amir of the Kakui dynasty- in 432 L.H (1041 A.D) (33) ۞, «Alaod Dowleh Amir Ali ebne Faramarz» and his wife -«Arsalan Khatoon»- between years 455 L.H (1063 A.D) to 488 L.H (1095 A.D) (34) ۞, «Amir Shamsod Din» -the son of «Amir chaqmaq»- and «Abul Ozra» -a «Gourkani»`s agent- in the decade of 850 L.H (1446 A.D) (35) ۞, «Khajeh Jalalod Din Mahmood Kharazmi» in 809 L.H (1406 A.D) (36) ۞, «Shah nezam Kermani» -the governor of Yazd under the «Timurid Shahrokh»- in 819 L.H (1416 A.D) (37) ۞, «Bibi Fatemeh Khatun» -the wife of Amir chaqmaq in 830 L.H (1427 A.D) or 836 L.H (1433 A.D) (38) ۞, «Khajeh Moinod Din Maybodi» -a minister of Yazd under the «Timurids» before the year 861 L.H (1457 A.D) (39) ۞, «Amir Nezamod Din Haji Qanbar Jahanshahi» in 862 L.H (1458 A.D) (40) ۞, «Mowlana Abdul Hayy» and «Mowlana Shahabod Din Abdollah» during the «Safavid» period before 1090 L.H (1679 A.D) (41) ۞, «Prince Mohammad Vali Mirza» in 1240 L.H (1825 A.D) (42) ۞ and «Seyyed Ali Mohammad Vaziri» in the year 1324 S.H (1945 A.D) (43) ۞.

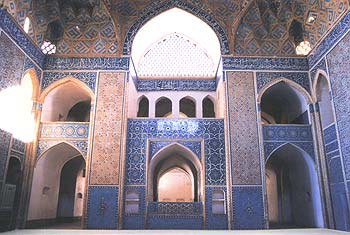

|  گنبدخانه مسجد جامع كبير يزد؛ كتيبه خوشنويسي سوره انا فتحنا دور فضاي زير گنبدخانه نيز گرديده است. Gonbad-khnae of Yazd great congregational mosque; Calligraphic inscreaption of Inna Fatahna surah also round around the under dome space. Moeen Mohammadi Various sources, as well as existing inscriptions, name the different architects involved in the construction of this mosque. These artists include: «Mowlana Afifod Din Memar» during the first half of the eight lunar hijri century (44) ۞, «Mowlana Ziaod Din Mohammad Memar» in 777 L.H (1375 A.D) (45) ۞, «Sonollah Memar Yazdi» in 947 L.H (1540 A.D) (46) ۞ and «Omar ebne Mahmood Haj Tajod Din» which his name appears in an undated inscription in the eastern portico (47) ۞. The architect of the dome was the architect from Yazd, «Saad ebne Mohammad Kadook», but the inscription of the dome bears no date. (48) ۞ The portico and minarets were restored in 1365 L.H (1945 A.D) by the architect from «Mehriz», «Hossein Ali Mahmoodi». (49) ۞

The calligraphers of the mosque`s inscriptions include: «Bahaod Din Hezar Asp» (50) ۞, «Mowlana Shamsod Din Mohammad Shah Hakim Khattat» (51) ۞, «Mowlana Kamalod Din ebne Shahabod Din» known as «Assar» in which two inscriptions dated 863 L.H (1459 A.D) and 875 L.H (1471 A.D) by him are visible in the eastern entrance vestibule and another inscription by the same calligrapher exist in the prayer niche of the gonbadkhaneh which although undated obviously belongs to the same period (52) ۞, «Soltan Mohammad» (53) ۞, «Noorod Din Mohammad Kachui» (54) ۞, «Abu Taleb» (55) ۞, «Zabihi» (56) ۞, and «Ali Mohammad Kaveh» (57) ۞. The inscriptions also give the names of their stone-carvers as «Mohammad Reza», «Soltan Mohammad Yazdi» and his son -«Mohammad Amin»-. (58) ۞

The name of the artist in charge of the superb tile-worked prayer niche of gonbadkhanrh, «Haj Bahaod Din Mohammad ebne Abi Bakr ebne Alhosseini», appears on its inscription dated 777 L.H (1375 A.D). (59) ۞ In the vestibule of the eastern entrance, a collection of tessellated tiles dated 820 L.H (1417 A.D) that could also be read as 982 L.H (1574 A.D) bears the name of «Qotbod Din Sayrafi». These tiles were unearthed from under the remains of the Garshasbi garmkhaneh. (60) ۞ The panels in the vestibule give the names of the building`s bequeathers as «Ebne Soltan Mahmood Haji Afzal» and «Khajeh Aminod Din ebne Hossein ebne Ali. (61) ۞

2-3- Information from written sources ۩

«Donald Wilber» has recorded that remains of an ancient mosque probably belonging to before the «Seljuq period» exist on the eastern side of the courtyard. (62) ۞ The ruins of this building were still in existence as late as a few decades ago and «Maxime Siroux» has included several pictures of them in his essay on the Jame Mosque of Yazd. (63) ۞

|  برش عمودي A - A از پلان مسجد جامع يزد. Section A - A from the plan of Yazd jame mosque. |

2-4- Evolution of the building ۩

The present-day mosque stands on the site of three mosques that had been built in the course of successive centuries and eventually transformed, in the «Qajar period», into a single edifice with a vast courtyard. The first mosque, i.e. «Atiq (64) ۞ Jame Mosque», was built in the second half of the third lunar hijri century, during the reign of Saffarid monarch Amr Leys, following a shabestan design. This mosque was repaired and restored in the second half of the fifth lunar hijri century, under the Kakui rulers of Yazd, and a minaret was erected beside it which remained standing until the ninth lunar hijri century. Remnants of the original mosque subsisted on the northeast of the present mosque`s courtyard until 1324 S.H (1945 A.D).

|  برش عمودي B - B از پلان مسجد جامع يزد. Section B - B from the plan of Yazd jame mosque. The second mosque, i.e. the «Qadim (65) ۞ Jame Mosque», was built under Alaod Dowleh Garshasb ebne Ali ebne Faramarz -one of the Kakui rulers of Yazd-. This mosque, the design of which comprised a gonbadkhaneh equipped with an eivan, was built on the western side of the Atiq Mosque; follwing which the daughters of Faramarz ebne Ali Kakui had a shabestan and a mausoleum erected beside it. This mosque existed until 1240 L.H (1825 A.D), when its major part was demolished during the renovation and enlargement of the ensemble.

The third mosque, i.e. the «No (66) ۞ Jame Mosque», was built in the first half of the eighth lunar hijri century by «Seyyed Roknod Din Mohammad Qazi» behind the qebleh (67) ۞ of the Qadim Jame Mosque. This mosque had a small courtyard and a huge gonbadkhaneh and eivan. (68) ۞ Maxime Siroux believes that this building was part of the project of a four-eivan mosque which was not carried out. (69) ۞ In 777 L.H (1375 A.D), Shah Yahya ebne Mozaffar`s building activities resulted in extensive decorative tile-work in No Jame Mosque and the construction of its eastern shabestan and massive portico. (70) ۞

In 809 L.H (1406 A.D), during the rule of «Khajeh Jalalod Din Kharazmi», the tile-work decoration of the mosque was continued. At this time, the writing of the «Inna Fatahna» surah around the square courtyard and the mosque`s eivan and gonbadkhaneh was begun, and completed in 819 L.H (1416 A.D), under Shah Nezamod Din Kermani, concurrently with the construction of the western shabestan and portico. (71) ۞ Shah Nezamod Din also had the caravansary opposite the mosque`s portico transformed into a forecourt. This forecourt had two central pools, as can be seen in the plan drafted by Maxime Siroux. (72) ۞

In 825 L.H (1422 A.D), during the rule of Amir Chaqmaq, restoration and renovation works were carried out in the Atiq Jame Mosque which continued until 846 L.H (1442 A.D). Maxime Siroux believes that the minarets of the main portico were probably built at this time. Another probability is that these minarets were added to the portico during the reign of Safavid Shah Tahmasb. Inscriptions belonging to this time are visible in the portico.

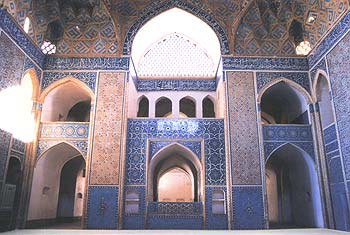

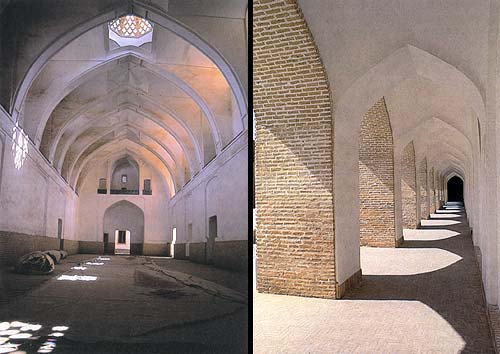

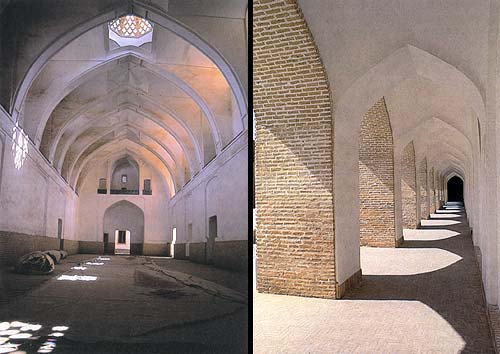

|  عكس راست: رواق شاهزاده محمد ولي ميرزا در جبهه هاي شرقي و شمالي و غربي حياط مسجد جامع يزد؛ عكس چپ: يكي از دو فضاي مجاور گنبدخانه يا رواق خواجه غياث الدين در مسجد جمعه يزد. Right picture: Prince Mohammad Vali Mirza colonnade on the eastern, northern and western sides of the courtyard of Yazd jame mosque; Left picture: One of two spaces adjoining the gonbad-khaneh or Khajeh Qiasod Din colonnade in Yazd friday mosque. Moin Mohammadi | |

During the reign of the «Qajar monarch Fath Ali Shah», extensive construction works were carried out in the mosque which resulted in the demolition of many parts of the three congregational mosques. At this time, the present Jame Mosque took shape as a single building. During the enlargment of the No Jame Mosque`s square courtyard and the demolition of three of its sides, part of the Quranic inscription around the courtyard were destroyed and today only parts of it remain on the southern side, the gonbadkhaneh and eivan. Also, major parts of the Atiq and Qadim congregational mosques were demolished and replaced by the No Jame Mosque`s courtyard. The remaining parts on eastern and western sides of the new courtyard were restored. Meanwhile, the northern portico of the mosque was rebuilt on the side of the entrance dating back to the reign of Garshasb. During the reign of «Qajar monarch Nasered Din Shah», the eastern shabestan, the main entrance vestibule, the tall minarets of the portico and the braces of the gonbadkhaneh were restored.

The building of the mosque has sustained heavy damage in recent times, but was restored in 1324 S.H (1945 A.D) upon the initiative of «Haj Seyyes Ali Mohammad Vaziri». At this time, the remains of the Atiq Jame Mosque, which had fallen into ruin besides the mosque`s courtyard, were demolished and replaced by a new shabestan. (73) ۞ | |  كتاب گنجنامه؛ دفتر 8، مساجد جامع، بخش دوم كتاب گنجنامه؛ دفتر 8، مساجد جامع، بخش دوم

با آنكه معماري اين سرزمين، تاريخي چند هزار ساله دارد، تلاش هايي كه براي شناسايي و معرفي آثار آن صورت گرفته است سابقه چنداني ندارد. تنها از چند دهه پيش محققان و پژوهشگران به بازنگري اين آثار هنري پرداخته و كوشيده اند گرد و غبار گذشت قرون را از اين گوهر هاي تابناك بزدايند و تلالو چشم نواز آنها را دوباره آشكار سازند.

علل و عوامل آن بي توجهي و نيز اين التفات ناگهاني به آثار تاريخي معماري بحثي مفصل مي طلبد كه در حوصله اين مختصر نمي گنجد. همين قدر بايد اشاره كرد كه آن بي توجهي در واقع محصول توجه كامل و اين التفات، نتيجه بي التفاتي است. چه تا آن زمان كه اين آثار جزيي از زندگي مردم ما بود، لزومي به شناخت و معرفي آنها احساس نمي شد؛ اما آنگاه كه بر اثر انقطاع فرهنگي، رشته هاي اصالت ديرين گسسته شد و نشانه هاي بي ريشگي در همه چيز ظاهر گشت، تمايل به بازگشت به خود و يافتن هويت خودي نيز فزوني گرفت؛ و به اين ترتيب، آثار معماري گذشته هم مانند هرآنچه از اصالت گذشته نشاني داشت، محتاج بازشناسي و معرفي شد. ناگفته پيداست كه راه اين بازشناسي و ادراك دوباره، سخت ناهموار و پرمخاطره است و بزرگترين سنگ اين راه نيز همان بريدگي فرهنگي و بيگانگي از خود است كه راست ها را كج مي نماياند و بيراهه ها را راه. به هر حال، امروز در وضعي قرار گرفته ايم كه لزوم شناسايي و درك آثار معماري گذشته بر هيچ كس پوشيده نيست. اين حقيقت اين اميد را پديد مي آورد كه انشاء الله روزي تك تك اين آثار گرانبها و ميراث غني گذشتگان ما كه در سرتاسر اين سرزمين پهناور پراكنده است، به نحوي شايسته و صحيح بازشناخته شود تا براي رسيدن هنرمندان و معماران آينده به استقلال شخصيت هنري و فرهنگي، چراغ راهي فراهم آيد.

مجموعه حاضر را بايد يكي از بلندترين گام هايي دانست كه تا كنون در راه معرفي آثار ناشناخته اين معماري برداشته شده است. اين مجموعه را «گنجنامه» ناميده ايم؛ چون بر اين باوريم كه نشانه هاي گنجي را ارايه مي دهد؛ گنجي كه دستيابي به آن، سرافرازي و استقلال در پي دارد. پديدآورندگان گنجنامه بر آن اند كه با كنار هم آوردن و ارايه يكجاي نقشه هاي كامل و خوانا و عكس هاي واضح و تاريخچه اي تنظيم شده، بر مبناي مهم ترين منابع انتشار يافته، از بيش از ششصد اثر مهم تاريخي، از مسجد و مدرسه گرفته تا خانه و حمام، هم راه تحقيق و پژوهش را در اين زمينه بگشايند و هم اسباب تشويق و ترغيب محققان و كارشناسان و علاقه مندان را براي مطالعه و تفحص در اين آثار فراهم آورند. نكته ديگر آنكه اين مجموعه يك شبه فراهم نشده است و محصول پشتكار و در حدود چهل سال تلاش استادان و دانشجويان «دانشكده معماري و شهرسازي دانشگاه شهيد بهشتي» است؛ و به اين ترتيب بايد گفت كه در حدود نيمي از دانش آموختگان هنر معماري در اين كشور در شكل يافتن گنجنامه سهيم بوده اند.

دفتر هاي گنجنامه ترتيبي موضوعي دارد؛ و اين مجموعه تقريباً همه انواع بنا را در بر مي گيرد: پنج دفتر مختص معرفي خانه هاي سنتي در شهر هاي مختلف شامل يك دفتر خانه هاي كاشان، يك دفتر خانه هاي اصفهان، يك دفتر خانه هاي يزد و دو دفتر خانه هاي شهر هاي ديگر؛ چهار دفتر شامل مساجد شامل يك دفتر مساجد اصفهان، يك دفتر مساجد شهر هاي ديگر و دو دفتر مساجد جامع؛ سه دفتر مربوط به امامزاده ها و مقابر؛ دو دفتر شامل بنا هاي بازار؛ يك دفتر ويژه مدارس؛ يك دفتر مربوط به كاروانسرا ها؛ يك دفتر خاص حمام ها؛ يك دفتر مختص كاخ ها و باغ ها؛ يك دفتر نيز استثنائاً شامل انواع بنا هاي مذهبي در تهران. فهرست هاي راهنماي مجموعه نيز در دفتر آخر خواهد آمد.

دفتر هاي هفتم و هشتم گنجنامه مختص معرفي مساجد جامع تاريخي ايران است. در تاريخ معماري ما، مسجد مهمترين بنا بوده است؛ و در ميان مساجد، مسجد جامع، اهميت ويژه اي داشته است. در تاريخ ما، هيچ شهري بدون جامع، شهر محسوب نمي شده و به عبارت ديگر، وجود جامع در شهر، حاكي از مدنيت آن بوده است. مسجد هم معبد و هم ميعادگاه مردم بود؛ و افزون بر آن، جامع، قلب و مركز شهر بود. جامع، هم جايگاه عبادت مردم، هم محل اجتماع و تبادل افكار و درس و بحث، هم جاي قضاوت و حل و فصل اختلافات، هم منزلگاه غريبان و مسافران و هم محل هنر آفريني هنرمندان و معماران بود. تبيين تاريخ معماري ما منوط به شناخت معماري مساجد است و افزون بر آن، شناخت معماري مساجد، منوط به مطالعه دقيق تاريخ مساجد جامع است.

مساجد جامع كه اصلاً براي اقامه نماز جمعه بنا گشته اند، اغلب، عمري طولاني دارند و تغيير و تحولات فراواني به خود ديده اند؛ هر روز، رنگي پذيرفته اند و از هر دوره، يادگاري دارند. به همين علت، كمتر مسجد جامعي مي يابيم كه تنها متعلق به يك دوره تاريخي باشد. بسيار اند مساجد جامعي كه در قرون اوليه هجري قمري پايه گذاري شده و در طي زمان، بر حسب مقتضيات و سلايق و پسند هاي روز، تغيير شكل يافته اند. به سبب همين دگرگوني هاي مداوم، معمولاً در تاريخچه و چگونگي سير تحول آنها، ابهام، و در نتيجه، اختلاف نظر بسيار وجود دارد. جامع ها، مانند موجوداتي زنده، به مرور زمان تغيير شكل يافته و با شهر رشد كرده و با آن دگرگون شده اند.

مساجد جامع، همواره قلب تپنده شهر هاي ما و مامن و ملجا مردم بوده اند؛ چه درد ها كه نشنيده اند؛ چه شادي ها كه نديده اند؛ چه مصيبت ها كه شاهد آن نبوده اند؛ چه روز ها كه با مردم نزيسته اند؛ چه بلوا ها و چه شورش ها و چه شكست ها و پيروزي ها كه نديده اند. از هر كسي اثري پذيرفته اند؛ از حاكمان و محكومان، ستمگران و ستم ديدگان، فاتحان و شكست خوردگان و .... در يك كلام، مساجد جامع، كهن بنا هايي اند كه هزاران سخن، بلكه تاريخي در سينه دارند. آنها پيراني هزار ساله اند كه براي مردم، قصه ها در دل دارند؛ و بايد گفت كه تاريخ راستين ما، تاريخ مساجد جامع است.كامبيز حاجي قاسمي؛ زمستان 1383

Book of Ganjname; Volume 8, Congregational Mosques, part two Although a past of several millennia lies behind the architecture of this land, it was only quite recently that efforts aimed at identifying and introducing its extant achievement were undertaken. Only a few decades have passed since scholars and researchers first began reviewing these works in order to wipe the dust from the face of these resplendent jewels and once again reveal their charming, familiar radiance. The factors involved in this long-standing neglect and the sudden interest in historic relies call for a more thorough discussion that falls beyond the scope of this brief exposition. It suffices to note that the neglect in question in fact resulted from total interest and that the newly emerged interest was the outcome of utter neglect, because, as long as these works were part of our people`s life, no need for introducing them was felt, but when, owing to a cultural rift, time-honored roots were severed and the signs of rootlessness became ubiquitous, an inclination toward rediscovering and reverting to our own identity increased, and the need for recognizing and introducing past architectural achievement, just like everything else that bore signs of past originality, became perceptible .But, needless to say, the path of this recognition and renewed understanding is arduous and fraught with dangers, the greatest obstacle being the very cultural rift and alienation which makes the straight path seem crooked and causes detours to appear as the main path. In any case, the present conditions are such that the necessity of identifying and understanding past architectural achievement has become obvious to all. This truth crates the hope that, God willing, every one of these valuable works of art and rich heritage of our ancestors scattered throughout this vast land will be adequately recognized, illuminating the path leading our future artists and architects towards artistic and cultural independence. The present collection must be considered one of the most significant steps yet taken in the direction of introducing the unknown accomplishments of this architecture. We have entitles it «Ganjnameh» that literally means «Treasure Book»; Because we believe that it bears clues to a treasure the acquisition of which will assure our dignity and independence. By bringing together complete and legible plans, clear and expressive images and thematic authentic history of more than six hundred significant historic realizations, ranging from mosques and madrasas to hoses and baths, the Ganjnameh seeks to not only initiate research in this domain but also encourage researchers, experts and all those interested to begin research of their own on these rich relics. Another point is that this collection was not brought into being overnight. Rather, it is the outcome of some forty years of relentless efforts on the part of the professors and student of the «Architecture and Urban Planning Faculty of Shahid Beheshti University». Therefore about a half of those who have studied architecture in this country may be said to have contributed to its creation. The volumes of the Ganjnameh follow a thematic order. The collection embraces almost every type of building: Five volumes introduce traditional house in various cities include one volume includes the houses of Kashan, one volume the houses of Esfahan, one volume the houses of Yazd and two volumes the houses of other cities; Four volumes cover mosques include one volume the mosque of Esfahan, one volume the mosques of other cities and two volume congregational mosques; Three volumes are dedicated to emamzadehs and mausoleums; Two volumes deal with bazaar building; One volume is dedicated to theological schools; One volume introduces caravansaries; One volume deals with baths; One volume concern palaces and gardens; One volume exceptionally introduces religious building in Tehran. The table of content of the entire collection will be included in the last volume. The seventh and eighth volumes of the Ganjnameh introduce Iran`s historic congregational mosque. Throughout the history of our architecture, mosques have been the most important type of building, with congregational mosques in particular enjoying an exceptional status. All along our history, no city was regarded as one unless it possessed a congregational mosque. In other words, the existence of a congregational mosque in a city was a sign of its urbanity. A mosque was not only a temple, a place of worship, but also a popular meeting place; in addition to that, a congregational mosque, in fact, embodied the heart and hub of a city. A congregational mosque was at once a place of worship, of social gathering, of education and discussion, of judging and solving problems, an abode for homeless strangers and travelers, and an arena for artists and architects to display their virtuosity. Any survey of the history of our architecture has to be based on studying the architecture of our mosques; in addition to that, studying the architecture of mosques must be based on a meticulous study of congregational mosques. Originally built house Friday prayers, most congregational mosques are quite ancient and have undergone many alterations in the course of time, taking on different colors and receiving additions in different periods. Hence, rarely is a congregational mosque found that belongs strictly to a single historic period. Built in the early centuries of the Islamic era, the majority of our congregational mosques were subsequently modified in accordance with changing tastes. In reason of this perpetual change, the study of their history and evolution is fraught with uncertainty and occasional gross disagreement. Just as living beings, they have undergone changes of appearance while growing together with their cities. Congregational mosques have ever been the beating heart of our cities and a safe refuge for people. Lo! How many pains they have heard of? How many joys they have looked at? How many tragedies they have witnessed? How many days they have lived with the people? How many riots and uprisings and how many defeats and victories they have gone through? All, whether ruler or ruled, oppressor or oppressed, conqueror or conquered, artist, architects and ... have left traces in them. In brief, ancient congregational mosques bear a thousand tales, nay, a full history, in their bosom. They are venerable relies who hold myriad accounts for the people to hear. In fact, our true history is that of congregational mosques. Kambiz Haji Qasemi; Winter 2004 |

| | | | ديدگاه هاي خوانندگان درباره اين مقاله: | 2 ديدگاه واپسين از 2 ديدگاه |

very very goooooooood

tanckssss 9/22/2010 11:33:26 AM

خيلي خوب بود. ولي مي تونين پرسپكتيو مسجد جامع را هم بگذارين؟ من واقعا نياز دارم. 11/15/2011 9:37:02 AM |

|

| هنگام چاپ: 3/30/2010 5:56:03 PM | امتياز: 3.94 از 5 در 17 راي | | شمار بازديد: 81286 | شمار ديدگاه: 2 |

|

|

|

كتاب گنجنامه؛ دفتر 8، مساجد جامع، بخش دوم

كتاب گنجنامه؛ دفتر 8، مساجد جامع، بخش دوم